As a graduate who had recently established his own business, Shay Emerton had much to look forward to when, in April 2021, he suffered a seizure whilst playing football and went into respiratory arrest. Luckily, an anaesthetist playing for the opposition was able to revive him and the 24-year-old, from St Albans in Hertfordshire, was rushed to hospital where scans revealed he had a brain tumour. In May he underwent surgery in which 98% of his grade 2 glioma was removed, but he suffered supplementary motor area (SMA) syndrome which left him with temporary paralysis down his right-hand side. He encountered a further setback when he developed an infection, however, he now feels like he is starting to get his life back and has even signed up to run next year’s London Marathon.

Shay tells his story …

I studied at the University of Bath and graduated in 2019 with a 2:1 in biochemistry. After I finished, I had planned to go to Australia with a friend for a few months but he wasn’t able to and it felt wrong to go without him so I was left not really knowing what to do. My family owns Burston Garden Centre, in St Albans, so I started working there temporarily and it was during that time that my best friend, Nick Gurney, returned home from two years in Australia where he’d been working as a landscape gardener. In January 2020 Nick and I discussed setting up our own landscape gardening business and, as I had grown up around the garden centre and loved the outdoors, it made complete sense. Initially, we thought it would just be a way to make some money on the weekends but it really took off and, after lockdown, we were busier than ever.

I was just living the life of a normal 24-year-old – busy working, having just completed a week-long tennis court project in Surrey, really fit, going to the gym six times a week and playing football on weekends, and enjoying seeing my friends and going to the pub for a couple of drinks here and there. Life was good. The night before everything happened, I’d been to the pub with Nick and remember saying to him that I was in the best shape of my life, the healthiest I’d ever been. On 11 April I woke up feeling fine and went to play football, as I did most Saturdays. The game was going well, we were 2-1 up and I’d even scored a goal, before the ball hit me hard in my head and I fell down. I remember thinking: ‘something’s not right here’ as my head went fuzzy. I felt as if I was on the verge of passing out and when I tried to stand up, my legs were shaking and I couldn’t.

“The first thing I worried about was having a brain bleed and I called out, saying ‘Dad, I’m in trouble’.”

“I thought they’d call an ambulance and I’d be fine, but then my whole body started shaking and I had a 10-minute grand mal seizure, during which time I went into respiratory arrest and stopped breathing.”

Luckily, the opposition had an anaesthetist playing for them – he’d never played before and was just standing in for a friend – and he gave me CPR on the pitch and got me breathing again. The next thing I knew I was waking up in the ambulance wondering what had happened. I thought I’d been knocked out but the paramedics told me I’d had a seizure, probably because I’d gone into shock. They asked me my dad’s name and I got it wrong. He’s called Andrew and I said it was Eddie. I’m not sure why I said that, I do have a very good friend by that name and even as I said it, I knew it wasn’t right but I couldn’t correct myself.

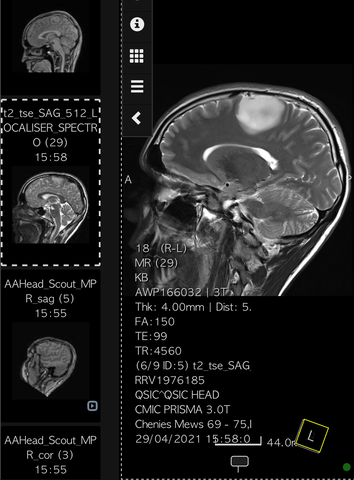

They took me to A&E at Watford General Hospital but I didn’t feel too bad by then. I had a bit of a headache but things were slowly starting to come back to me; I remembered my dad’s name and that I’d been playing football. A doctor took a CT scan, which obviously showed something up because he said he wanted ‘to check on something’ by doing an MRI, so I was also given an MRI with contrast. This was at a point where, because of COVID-19, hospitals still weren’t allowing visitors in so when I saw my mum, Dawn, and my dad I instantly knew something was wrong. I immediately thought ‘please don’t let it be a brain tumour’ and then the doctor said ‘I’m sorry to tell you you’ve got a mass on your brain’.

“I think he must have seen the panic on my face because he told me the fact the contrast hadn’t lit anything up was a good sign.”

My scans were sent for review to the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery (NHNN) in Queen Square, London, which took three days and meant that I was stuck waiting for Watford General to get the okay to discharge me. Obviously, all the worst-case scenarios went through my head but I hoped I’d be ok. I kept thinking that as the contrast hadn’t absorbed anything maybe it wasn’t cancer. I was young, I hadn’t had headaches or felt sick and was in prime fitness. Six years earlier I’d suffered a collapsed left lung having been born with a weakness in it. At the time I thought I was having a heart attack and ever since then I’ve been really health conscious. Eventually I was discharged and told that I needed to go to Queen’s to meet a neurologist. I still thought they would be able to remove it and after a bit of recovery time I’d go back to normal, like with my lung operation.

“Telling my friends was one of the hardest things to do because I didn’t have any answers and didn’t know what the future held at that point.”

It sounds silly but I was also a little embarrassed about my diagnosis because I didn’t want people to see me differently – I’d always been the sporty adventurous guy and I didn’t want to be the potentially disabled brain tumour cancer patient.

I went to Queen Square the following week and met Professor Andrew McEvoy, a world-leading consultant neurosurgeon who is simply amazing. I was ready to turn up and have him put his arm around me and tell me he’d whip this thing out my head so I could get on with my life, but he was so professional and told me that he needed to do lots of his own tests before making any projections or even talking about surgery. I understand why he said that as he only had the one scan taken at Watford General on a Saturday night to go by, but I left that meeting in a worse place mentally than when I went in, thinking ‘maybe it is bad, maybe I only have six months to live.’ He organised a scan for me the following week but I had to wait another week after that to see him again so that was tough. I kept going back and forth with my thoughts; one minute I’d convince myself that everything was going to be fine and the next I’d be thinking about what I’d do if it was bad news. The only thing that got me through it was thinking about the contrast because I thought if what I had was malignant it would have been absorbed.

Professor McEvoy was much more positive the second time we met. He’d run the tests he wanted and was able to give me more information. He told me my tumour was located next to my primary motor cortex and was operable. Having an inoperable tumour was one of my biggest fears at that point so that was a relief but he did tell me there was a high risk of me being left disabled or with permanent deficiencies as a result of the operation which was really scary because I was so active and had no idea what I’d do if I couldn’t play football, cricket or golf ever again. He told me he thought I had a low-grade glioma and the plan would be to carry out a maximal safe resection without impairing my quality of life. I’d always known I wanted to have children in my future and, although he couldn’t tell me what to do, it was clear that having the surgery was my best chance at being able to have a family one day so I decided to go ahead with it.

“It took me about 30 seconds to make up my mind and I never looked back.”

After confirming my decision the following week, my operation was scheduled to take place six weeks later, a delay apparently brought about by a backlog of cases due to COVID-19, which meant it would happen on 12 July, my mum’s birthday. Until then I was told to go and enjoy my summer, which was easier said than done. By then I knew that I would be awake for the surgery, that there were a lot of risks in going through with it and that I wouldn’t be cured afterwards because they wouldn’t be able to get all the cells, but I carried on as best I could. I went to work and spent time with my friends and family, all the while knowing I was walking around with this plum-sized tumour in my head. My anxiety really started to kick in with me thinking I was having a seizure or a stroke every time I felt any pain. At one point my foot started tingling and I thought that was it. I couldn’t live my life knowing it was there, which was further confirmation that I had made the right decision to go ahead with the surgery. Luckily, the Euros were on which provided a great distraction and if I wasn’t watching football with friends, I was going on a dog walk and generally getting out as much as I could.

I was admitted to the NHNN on 11 July because Professor McEvoy wanted to start operating early the next day. It sounds ridiculous now but that night was probably my lowest point; the Euros final was on and I knew all my friends were out having a great time and I was stuck in a hospital getting ready to have brain surgery, thinking: ‘this isn’t what a 24-year-old should be doing’. My mum and dad couldn’t come in so I was left completely alone with my thoughts.

“I can’t explain the level of fear I felt that night as I contemplated a surgery I might not wake up from or which might leave me paralysed; I was in bits.”

I felt more at ease after seeing Professor McEvoy’s big smile the next morning. He was so confident that I thought: ‘well, if he’s not worried, I shouldn’t be either’. I felt like I was in safe hands and just wanted to get on with it. He reiterated that I would be woken up during surgery and asked to move various body parts on my right-hand side to make sure he was taking out my tumour and not healthy brain cells, thereby reducing the chance of being left with a permanent deficiency. He warned me that as he would be working in my supplementary motor cortex, I would be likely to suffer from supplementary motor area (SMA) syndrome which causes temporary paralysis as your brain shuts down parts to focus on other things as it figures out what’s going on. Time seemed to pass really slowly after that, even though it was only about an hour until I was taken into theatre.

My surgery started at about 8.30am and was supposed to take around eight hours. When I was woken up, I looked at the clock and remember thinking ‘good, it’s 12.30pm, we’re half way through’. It took me a bit of time to adjust and the anaesthetist was lovely and held my hand which I really appreciated. For the next two hours I was asked to move my fingers, hand, arm, leg and toes on my right-hand side. I could do it but then they said they were going to take a 15-minute break so I could relax as they didn’t want me to overdo it. I closed my eyes for a bit and then Professor McEvoy asked if I could lift my arm. I told him I could and had just done it so he asked if I could move my fingers and I couldn’t. He explained that they took a break because he saw my brain swelling in an area that would cause me to lose feeling and he didn’t want me to panic.

“I had lost complete function of everything down my right-hand side and, as much as they said it was going to come back, there was still a part of me that didn’t believe them.”

They put electrodes on my leg to see if the pathways were working. I could feel them buzzing when he touched parts of my brain, which was proof the function was still there and that’s when I relaxed a bit. The operation continued and I dozed off here and there and then had an MRI at the end. I asked how much they had removed and Professor McEvoy said they’d got at least 98%. He had a big smile on his face and said it had gone unbelievably well, even better than he could have hoped for, which was a great way to end the operation. He said there was still something showing up on the MRI but when he stimulated that area it stimulated the electrodes in my leg so he knew he couldn’t take it out without me losing the function in my leg.

I woke up to a grinding sound as they were screwing my head back together and the next thing I knew I was in the ICU. It was about 8pm, which was four hours later than I’d expected it to be and I knew that my parents would be worried. I had lost my speech as a result of the SMA and it took a lot of effort to communicate but I told Professor McEvoy it was my mum’s birthday and asked if he could call her. I remember hearing my mum crying through the phone as he gave her the news. I said: ‘happy birthday Mum, I’ve done it’ and then fell asleep as it was all a bit much. I spent the next few days lying in hospital having weird dreams because of all the pain medication I was on.

“The day after the operation I said I felt okay but Professor McEvoy told me the pain was coming and he was right; when it came it was excruciating.”

When I still couldn’t move after a few days, I started to panic. Professor McEvoy came to see me every day and reassured me but it was disconcerting not being able to move anything but my neck. I was told to give it time as my brain needed to recover from having a large hole made in it and was assured it would come back. On the morning of the fourth day, I woke up about 10am and couldn’t get back to sleep so I decided I was going to make my body move. I spent about six hours starring at my finger and it worked so I sent a video of me scratching my pillow to my mum. After that I wasn’t worried because I knew if I could get that back everything else would come. I asked if I could see my mum and was moved to private room so she could visit. We both cried for the first half hour but then the rest of the time was spent with me showing her all the things I could do by moving my fingers and just about raising my hand. The rest of my movement came back quite quickly after that.

“By the afternoon I was able to pick up a glass of water and bring it to my mouth so that felt like quite an achievement.”

The next night, my sixth after surgery, I woke up needing a wee and got out of bed without even thinking about it, but, even though I was standing, I realised I couldn’t walk and had to call a nurse. Once I knew I could do it, though, I was able to do it again and again. Once the pathway was reconnected, that was it. The following day Professor McEvoy had heard about me standing and asked me to show him. By that point I was getting frustrated because the weather was nice and I wanted to go home, but he said I had to be able to walk first. A week after my operation, the physios came to see me and I told them that I wanted to walk that day. They were only supposed to be with me for 30 minutes but they must have sensed how determined I was because they spent two hours with me and by the end of it, I was walking.

“Once I could walk, I felt human again and felt like I was finally on my road to recovery.”

I spent the rest of the day showing off I could walk and in the end I was told to sit down to avoid tiring myself out. I had to stay one day longer because patients are at greater risk of having a stroke during the first 10 days post-surgery, but after that I was free. I was offered a wheelchair but I turned it down because I wanted to walk out of the hospital, but by the time I got to the car I more or less fell into it. Still, I was absolutely ecstatic and spent the day in the garden, which is when the enormity of my situation hit me. I’d gone through a massive operation, learned to walk and talk again and still wasn’t cured. I knew my journey wasn’t complete and I would likely have to go through it all again someday, whether six months or 10 years from then. I knew my tumour wasn’t aggressive, which is why I didn’t have to undergo chemotherapy or radiotherapy, but I knew it was still there and would start growing again someday which left me with a mix of emotions.

I decided to focus on my recovery, on getting my movements back, because I still couldn’t manage more complex movements like eating and showering. It took me three months to be able to move my ankle and, even now, small movements like touching my fingers against my thumb require a lot of concentration and take longer. I was shattered, too. The days I should have been resting I was concentrating on moving and walking as much as possible, which meant later in the day I had lost the ability to hold a conversation so I wasn’t great company in the evenings for the first month or so after getting home.

We’ve got a holiday home on the Isle of Wight and so I asked my mum if we could go there and relax, which we did for a week. I spent time sitting down doing crosswords and without thinking about it I was teaching myself to write again. It was a lovely break but when we got back, I noticed my head had sort of ballooned. I had a bit of fluid after surgery, post-op fluid to protect the bone, but it had come back quite badly. I felt fine but obviously I was a bit concerned about it so I rang Professor McEvoy and he was away but I was given an appointment with his junior two days later. She felt it and said she thought it was just a protection layer and sent me away again.

I had a nice weekend but on the Monday I woke up and didn’t feel great. I felt a bit ‘off’ and my legs were really achy and I thought I must have been doing too much. By the Wednesday, Mum thought it best to go back to the NHNN to get checked out. By then it had been over a week and I saw the concern on the junior doctor’s face. When she pressed it, a bit of puss came out of my scar and she told me it was infected and admitted me straight away so I could start IV antibiotics. I wasn’t allowed to eat for two days, in case the antibiotics didn’t work and I needed to have surgery, but I started feeling better and the swelling started to go down.

After a week in hospital I was becoming increasingly frustrated at being stuck there without being able to work on my movements so much. I told them it was having a negative effect on my physical and mental health and asked if I could go home as long as I returned every day to have the antibiotics administered. They agreed after arranging for me to have a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC line) fitted and for 15 days I had to travel to London to get the antibiotics. My dad drove me into Central London every morning in rush hour traffic and my mum would accompany me inside for my appointments at 9.30am. Even after that finished, I had another two weeks of oral antibiotics which I had to take four times daily.

“It was in September, after I’d finished the IV antibiotics and was able to start seeing friends again, that I felt like I was able to start getting my life back.”

I finally returned to the gym, too. I had tried to go back earlier but just couldn’t walk through the door. I didn’t feel like a normal 24-year-old and think I’d been grieving my old life. It’s a weird thing to feel like you have no control over your life but I watched a video of Dave Bolton, a long time glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) survivor who was back in the gym despite having been through a hell of a lot more than me so I felt inspired to try again and two weeks ago I did it and loved it. I was happy, not just because of the endorphins it produces but because I felt in control again. I’ve spoken to Dave on a Zoom call since and think he’s really inspiring. He told me to accept what’s happened in the last eight months and not let it ruin the next 10 years. He said I was lucky to be given a second chance and to imagine what I could do in the next five years, which has motivated me to share my story. When I was first diagnosed, I was looking for hope and now I want to be able to give that to other people with a brain tumour diagnosis who have had their lives turned upside down.

If I hadn’t been hit by the ball on that fateful day, I could still be living my life without knowing about my tumour so in that sense I’ve got a head start on it. I’ve decided that I don’t want to live a compromised life because I’m worried about what could happen; I want to make the most of it. I still have to have a rest day here and there because my body goes into overdrive and I feel fatigued but I’m getting back out again and am looking forward to 12 July 2022, when I should be allowed to get my driving licence back. I’m living a relatively normal life but I’ve got this thing that will never leave me unless we find a cure, which is why I decided to run the London Marathon next year with my older brother, Connor. I really wanted to get back into health and fitness and knew the marathon would motivate me to start running. Thankfully we were both successful in securing places, which we’re really grateful for and will be running in aid of Brain Tumour Research.

“For me, to go from being paralysed down one side and unable to walk to running the London Marathon next year will be a great achievement.”

Shay Emerton

December 2021

Brain tumours are indiscriminate; they can affect anyone at any age. What’s more, they kill more children and adults under the age of 40 than any other cancer... yet just 1% of the national spend on cancer research has been allocated to this devastating disease.

Brain Tumour Research is determined to change this.

If you have been touched by Shay’s story you may like to make a donation via www.braintumourresearch.org/donate or leave a gift in your will via www.braintumourresearch.org/legacy

Together we will find a cure